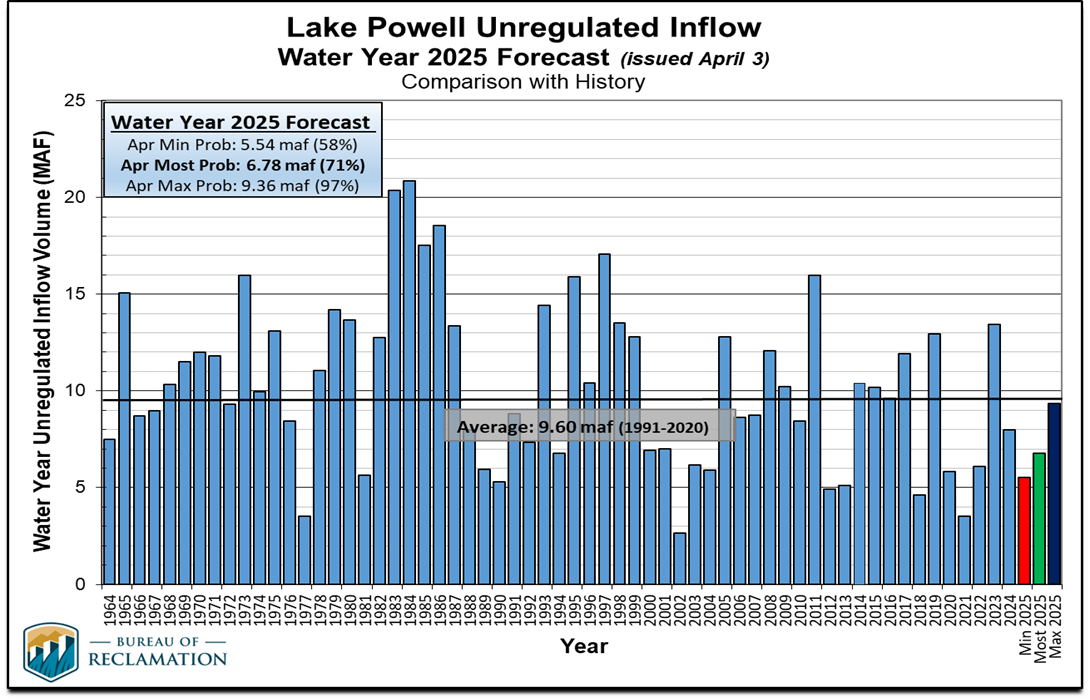

This looks like a water management issue. The level of Lake Powell depends on inflow and outflow. Inflow is determined by Mother Nature, and the Bureau of Reclamation reports that unregulated (i.e. adjusted for the effects of operations at upstream reservoirs) inflow is variable but not conspicuously declining over the decades. There was some difficulty in filling the reservoir when the dam was completed in 1963 because inflow was unusually low, but the lake was eventually filled by restricting outflow to 1,000 cubic feet per second -- just 0.74 million acre-feet per year in the units of the above chart. Today restricting outflow that much would cause problems for the much larger agricultural and population centers that are now downstream. But downstream consumption could be more efficient. 5.4 trillion gallons is 16.5 million acre-feet, more than the Lake Powell inflow in all but the wettest years.

The seven Colorado River states (Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming) and Mexico divide up rights for 5.4 trillion gallons of river water each year — 1.4 trillion more than has actually flowed through the river each year on average since 2001 and 500 billion gallons a year more than the river produced, on average, long before the drought.

"When we have it, we'll use it," he said. "You'll open your head gate all the way and take as much as you can — whether you need it or not." Ketterhagen feels he has little choice. A vestige of 139-year-old water law pushes ranchers to use as much water as they possibly can, even during a drought. "Use it or lose it" clauses, as they are known, are common in state laws throughout the Colorado River basin and give the farmers, ranchers and governments holding water rights a powerful incentive to use more water than they need.